What Meniere’s Disease Really Is

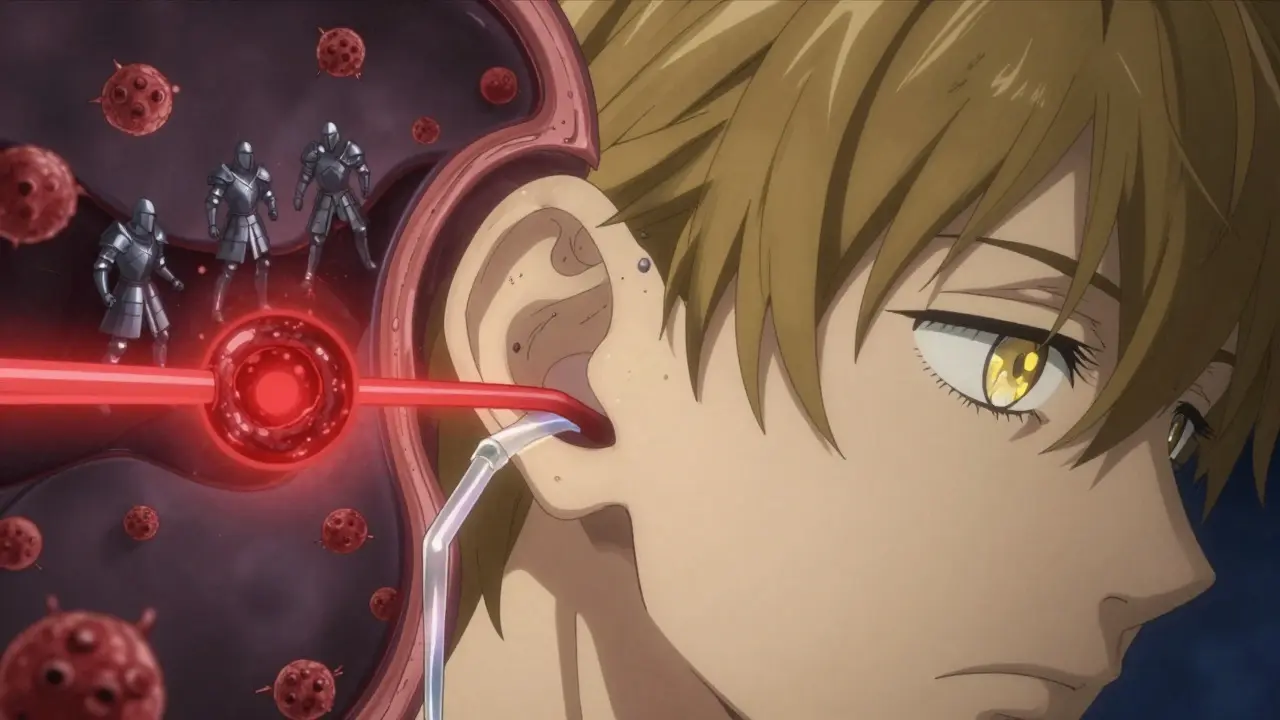

Meniere’s disease isn’t just dizziness. It’s a slow, unpredictable breakdown in your inner ear’s ability to manage fluid. The problem starts with endolymph - a potassium-rich fluid that fills the membranous labyrinth, including the cochlea and balance organs. In a healthy ear, this fluid moves just enough to send clear signals to your brain about sound and position. But in Meniere’s, too much of it builds up. This swelling, called endolymphatic hydrops, stretches the delicate membranes inside your ear, messing up the signals. That’s when vertigo hits - sudden, spinning, and often violent.

It’s not just about balance. Your hearing takes a hit too. The cochlea gets squeezed, and hair cells that turn sound into nerve signals start dying. Tinnitus - that ringing or roaring in your ear - becomes constant. And many people describe a feeling of fullness, like their ear is stuffed with cotton. These symptoms don’t come every day. They come in waves: hours of misery, then days or weeks of relative calm. But over time, the calm gets shorter. The attacks get worse. And the hearing loss? It doesn’t bounce back.

The Hidden Fluid System in Your Ear

Your inner ear isn’t one big water balloon. It’s two separate fluid systems working side by side. There’s endolymph, packed with potassium, flowing through the cochlear duct and semicircular canals. And then there’s perilymph, rich in sodium, filling the space around it. These fluids don’t mix. They need to stay balanced. If one leaks or overflows, everything goes wrong.

Endolymph is made mostly by the stria vascularis - a tissue in your cochlea that acts like a tiny kidney. That’s why cutting salt helps. Less sodium means less fluid production. Studies show reducing daily sodium to 1,500-2,000 mg can drop endolymph volume by 23-37%. The excess fluid usually drains through the endolymphatic sac, a small pouch near the back of the ear. But in 78% of severe Meniere’s cases, this sac is physically narrowed - sometimes down to 0.3mm wide. That’s like trying to drain a bathtub through a straw.

Recent 3D imaging has shown something startling: the membranes around the saccule (a balance organ) are thinner than those around the cochlea. That’s why swelling starts there - it’s the weakest point. The utricle, another balance organ, rarely swells early on. Only when the disease is advanced does it get involved. And there’s a valve, called Bast’s valve, that’s supposed to control pressure entering the utricle. In people with severe symptoms, this valve is either stuck open or torn. It’s not a mystery anymore. It’s anatomy.

Why Your Immune System Might Be the Real Culprit

For decades, Meniere’s was thought to be just a plumbing problem. But new research points to something deeper. In 2025, scientists found that inner ear fluid in Meniere’s patients is flooded with inflammatory chemicals - IL-12, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 - all at levels 4 to 5 times higher than normal. These aren’t random spikes. They’re signs your immune system is attacking your own ear.

Immune cells called dendritic cells and T-cells invade the inner ear, breaking down the blood-labyrinth barrier. This barrier normally protects the ear from blood-borne toxins and immune cells. Once it’s compromised, inflammation becomes chronic. Over time, this triggers fibrosis - scar tissue forms in the endolymphatic sac, making drainage even harder. That’s why some people keep having attacks even after cutting salt and taking diuretics. Their body isn’t just making too much fluid. It’s actively preventing it from leaving.

Biopsies from the NIH show that in 68% of long-term cases, Reissner’s membrane - the thin wall separating endolymph from perilymph - bulges into the helicotrema, the narrow passage connecting cochlear chambers. At pressures over 60 cmH₂O, this membrane can rupture. That’s when hearing loss becomes sudden and permanent. The immune response isn’t just a side effect. It’s a driver.

How Symptoms Change Over Time

Meniere’s doesn’t stay the same. It evolves. In the early stage, you get sudden vertigo attacks - maybe once a month - with hearing loss that comes and goes. Tinnitus flares up during attacks but fades afterward. You might feel fine between episodes. This is the “fluctuating” phase.

After 3-5 years, the hearing loss becomes more stable. It doesn’t bounce back. The vertigo attacks might still happen, but they’re often less intense. That’s not improvement. It’s progression. The inner ear is filling up. The fluid pressure is constant. The membranes are stretched thin. The hair cells are dying.

By the 10-year mark, 38% of patients stop having violent vertigo attacks. That sounds good - until you realize why. The ear is completely swollen. There’s no more pressure change to trigger the spinning. But now you’re constantly unsteady. Walking feels like walking on a boat. You can’t trust your balance. And your hearing? By then, 72% of patients have lost more than 50 decibels - enough to make normal conversation difficult without hearing aids.

Some people develop “vestibular Meniere’s” - vertigo without hearing loss. It makes up about 18% of cases. These patients often respond better to balance therapy because their cochlea is still relatively intact. But the underlying fluid problem? It’s still there.

First-Line Treatments: What Actually Works

Doctors start simple. Two things: low-sodium diet and diuretics. Cut sodium to 1,500-2,000 mg per day. That means no processed food, no canned soups, no soy sauce. Read labels. A single bag of pretzels can blow your daily limit. Studies show this alone reduces attacks in 55-60% of people.

Diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide help by reducing fluid production - just like they do in your kidneys. But here’s the catch: only 55-60% of patients respond. Why? Because if your endolymphatic sac is too narrow, the fluid can’t drain no matter how much you reduce production. The drug might help a little, but it won’t fix the blockage.

For vertigo attacks, doctors often prescribe meclizine or diazepam - but these are only for short-term relief. They calm your brain during an attack, but they don’t touch the root cause. They’re like putting a bandage on a leaky pipe.

Advanced Treatments: Injections and Surgery

If diet and pills don’t cut it, the next step is an injection. Intratympanic corticosteroids - like methylprednisolone - are injected directly into the middle ear. The medicine seeps through the round window into the inner ear. It reduces inflammation, calms the immune response, and helps regulate fluid transport. Studies show it controls vertigo in 68-75% of cases, with minimal risk to hearing.

For people who don’t respond to steroids, gentamicin injections are an option. This antibiotic is toxic to the balance system. It selectively destroys the vestibular hair cells - the ones causing the spinning. It works - 85-92% of patients stop having vertigo. But it comes with a price: 12-18% risk of permanent hearing loss. It’s a trade-off: lose a little hearing to stop the spinning.

Surgery is last-resort. Endolymphatic sac decompression opens up the sac to improve drainage. It helps vertigo in 60-70% of cases. But hearing? Only 25-35% improve. Vestibular nerve section cuts the balance nerve - stops vertigo, preserves hearing. But it’s major surgery, with risks of infection and facial nerve damage.

The Future: Targeting Immunity and Early Detection

The most exciting breakthroughs are happening in immunology. A 2025 clinical trial tested an anti-IL-17 antibody - a drug already used for psoriasis and arthritis. In Meniere’s patients, it cut vertigo attacks by 63% and slowed hearing loss by 41%. That’s huge. It means we’re finally treating the disease, not just the symptoms.

Another advance is early detection. Using 3D MRI scans, doctors can now see endolymphatic hydrops before symptoms even appear. Sensitivity is 89%. That means we could start treatment years earlier - before hair cells die, before hearing is damaged. Imagine catching it when your hearing is still normal, and stopping it before it starts.

Genetics is also revealing clues. Mutations in the SLC26A4 gene - linked to inner ear development - are found in 12% of families with Meniere’s. That’s not a cure, but it helps identify who’s at risk. If you have a close relative with Meniere’s, you might want to get screened.

Living With Meniere’s: Daily Strategies

You can’t cure Meniere’s yet. But you can control it. Here’s what works for people who’ve lived with it for years:

- Track your triggers: Stress, caffeine, alcohol, and sleep deprivation make attacks worse. Keep a journal. Notice patterns.

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration makes fluid imbalance worse. Drink water, but avoid sugary drinks.

- Balance training: Vestibular rehab therapy helps your brain adapt to imbalance. It doesn’t fix the ear - but it helps you move without falling.

- Reduce screen time: Bright, flickering screens can trigger dizziness. Use night mode. Take breaks.

- Don’t ignore anxiety: The fear of the next attack is exhausting. Therapy, mindfulness, and support groups help more than you’d think.

Meniere’s is not a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition - like diabetes or hypertension. It needs daily management. The goal isn’t to be perfect. It’s to reduce attacks, protect your hearing, and keep moving.

When to See a Specialist

If you’ve had more than two unexplained vertigo attacks in six months - especially with hearing loss or ringing in one ear - see an ENT who specializes in vestibular disorders. General doctors often misdiagnose Meniere’s as migraines or inner ear infections. But the treatment is completely different.

Ask for: a hearing test (audiogram), an ENG or VNG balance test, and an MRI to rule out tumors. If your doctor says, “It’s probably just stress,” get a second opinion. Meniere’s is real. And it’s treatable - if caught early.