When dealing with urinary health, overactive bladder is a condition characterized by a sudden, uncontrollable urge to urinate, often accompanied by frequency and nocturia frequently coexists with Pelvic Organ Prolapse, a descent of pelvic organs such as the bladder, uterus, or rectum into or beyond the vaginal canal.

Key Takeaways

- Overactive bladder (OAB) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) share risk factors and can worsen each other.

- Symptoms overlap, making accurate diagnosis essential.

- Management starts with lifestyle tweaks and pelvic‑floor therapy before considering medication or surgery.

- Individualized treatment plans improve quality of life and reduce recurrence.

What Is Overactive Bladder?

Overactive Bladder is defined by urgency, frequency (more than eight times a day), nocturia (waking up to pee), and sometimes urge urinary incontinence. It is not caused by infection, stones, or tumors, which is why doctors call it “idiopathic” when the cause is unclear.

Typical risk factors include age (especially after 50), caffeine or alcohol intake, diabetes, neurologic conditions, and a history of urinary tract infections. The bladder’s detrusor muscle contracts too early, sending a strong signal that the bladder is full even when it isn’t.

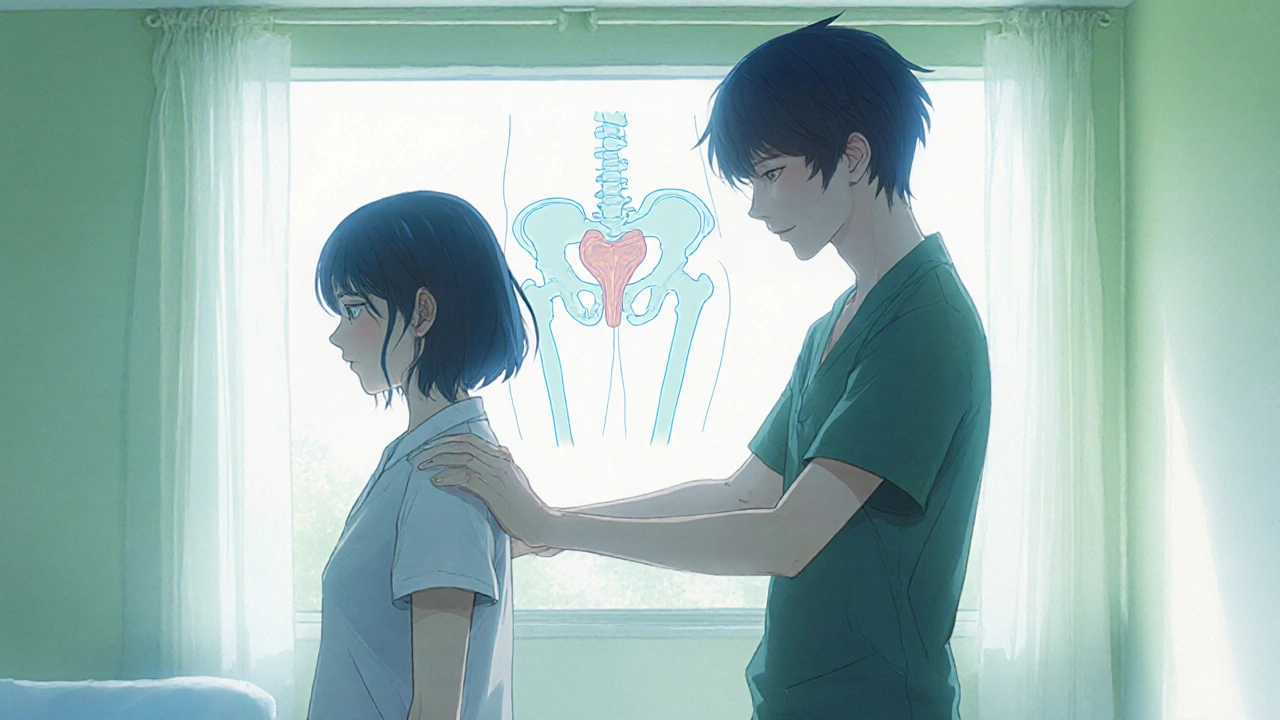

What Is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pelvic Organ Prolapse refers to the dropping of one or more pelvic organs-bladder (cystocele), uterus (uterine prolapse), rectum (rectocele), or small intestine (enterocele)-into or out of the vaginal canal. The supporting ligaments and muscles of the pelvic floor lose strength, often after childbirth, chronic coughing, or heavy lifting.

The degree of prolapse is staged from I (mild) to IV (severe) using the POP‑Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification) system. Symptoms range from a feeling of heaviness to visible bulging and, crucially, urinary disturbances.

How the Two Conditions Overlap

Because both OAB and POP involve the bladder’s position and function, they frequently appear together. A cystocele (bladder prolapse) can stretch the urethra, disrupting normal bladder signaling and creating urgency. Conversely, chronic urge to void can increase intra‑abdominal pressure, worsening a pre‑existing prolapse.

Key overlapping symptoms include:

- Sudden, strong urge to urinate.

- Frequent trips to the bathroom, especially at night.

- Leakage that occurs before reaching the toilet (urge urinary incontinence).

- A sense of pressure or a “lump” in the vaginal area.

Distinguishing whether urgency stems from pure OAB or from a cystocele is vital, because treatment pathways differ.

Diagnosing the Combo

The diagnostic work‑up typically follows these steps:

- History and symptom questionnaire - clinicians ask about frequency, urgency, leakage episodes, and any sensation of vaginal bulging.

- Physical examination - a gentle vaginal inspection using the POP‑Q system grades the prolapse.

- Bladder diary - patients record fluid intake, void times, and leakage for three days to quantify urgency and volume.

- Urodynamic testing - measures bladder pressure and capacity, helping to separate pure OAB from obstruction caused by prolapse.

- Imaging (ultrasound or MRI) - rarely needed, but useful for complex cases or planning surgery.

When both conditions are confirmed, the clinician can tailor the plan to address them simultaneously.

Management Strategies

Therapeutic options fall into three broad tiers: lifestyle & behavioral, medical/device, and surgical. The choice depends on symptom severity, prolapse stage, patient age, and personal preferences.

1. Lifestyle and Behavioral Interventions

- Bladder training - gradually increasing the interval between bathroom trips, starting with a comfortable schedule (e.g., every 2‑3 hours) and extending it by 15‑minute increments.

- Fluid management - limiting caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drinks while ensuring adequate hydration (≈1.5‑2 L/day).

- Weight control - losing even 5‑10 % of body weight can reduce intra‑abdominal pressure.

2. Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy focuses on strengthening the levator ani and coccygeus muscles, improving support for the bladder and uterus. A certified therapist teaches:

- Kegel exercises performed correctly (targeting the pelvic floor, not the abdominal muscles).

- Biofeedback or EMG devices that show real‑time muscle activation.

- Coordination drills that integrate breathing and core stability.

Studies show that 60‑70 % of women report reduced urgency after a 12‑week program.

3. Medical Options

- Antimuscarinics (e.g., oxybutynin, solifenacin) - relax the detrusor muscle but may cause dry mouth.

- β3‑agonists (mirabegron) - increase bladder capacity without anticholinergic side effects.

- Topical estrogen - for post‑menopausal women, improves urethral mucosa and may reduce urgency associated with POP.

4. Devices and Minimally Invasive Techniques

- Pessary - a removable silicone device placed in the vagina to support the bladder and reduce prolapse‑related urgency.

- Botox injections - injected into the detrusor muscle to suppress involuntary contractions (generally lasts 6‑9 months).

5. Surgical Options

Surgery is considered when conservative measures fail or when prolapse is stage III‑IV. Options include:

- Anterior colporrhaphy - stitches the front vaginal wall to support a cystocele.

- Mid‑urethral sling - a mesh‑less tape placed under the urethra to treat stress urinary incontinence, often combined with POP repair.

- Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy - attaches the vaginal vault to the sacrum using mesh, providing robust support for severe prolapse.

Comparison of Conservative vs. Surgical Approaches

| Aspect | Conservative (Lifestyle, PT, Meds) | Surgical (Repair, Sling, Sacrocolpopexy) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of relief | Weeks to months | Days to weeks |

| Invasiveness | Non‑invasive | Invasive (anesthesia required) |

| Risk of complications | Low (medication side‑effects, compliance) | Moderate‑high (infection, mesh erosion, pain) |

| Long‑term durability | Variable; may need ongoing therapy | High when surgery is successful (70‑80 % long‑term resolution) |

| Cost (UK NHS context) | Low to moderate (physio sessions, meds) | Higher upfront; may be offset by reduced repeat visits |

Choosing the Right Approach - A Quick Checklist

- Confirm diagnosis with bladder diary and POP‑Q exam.

- Assess severity: mild POP (stage I‑II) often responds to pelvic‑floor PT; severe (stage III‑IV) may need pessary or surgery.

- Consider comorbidities: diabetes or neurologic disease may limit surgical options.

- Review medication tolerance: anticholinergic side‑effects vs. β3‑agonist suitability.

- Discuss personal goals: desire to avoid surgery, willingness for long‑term therapy, or need for rapid symptom relief.

- Plan follow‑up: re‑evaluate symptoms after 6‑8 weeks of conservative care before escalating.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can overactive bladder cause pelvic organ prolapse?

The urge to void can increase intra‑abdominal pressure, which over time may weaken pelvic‑floor support and contribute to prolapse, especially in women who already have a weak floor.

Is a pessary a permanent solution?

No. A pessary provides temporary mechanical support. It must be fitted by a clinician and cleaned regularly. Many women use it while preparing for surgery or as a long‑term non‑surgical option.

What are the side‑effects of bladder‑training exercises?

There are none beyond mild frustration if the schedule feels restrictive. The key is gradual progression and using a bladder diary to track improvement.

Do hormone‑replacement therapies help with OAB and POP?

Topical vaginal estrogen can improve urethral tissue quality and reduce urgency in post‑menopausal women, but it does not correct anatomical prolapse. Systemic hormone therapy may have broader benefits but carries its own risk profile.

How long does recovery take after POP surgery?

Most patients resume light activities within 4‑6 weeks. Full recovery, including return to heavy lifting or intense exercise, may take 3‑4 months. Follow‑up appointments ensure proper healing.